Home » Legal Futurism (Page 4)

Category Archives: Legal Futurism

Big Data and Preventive Government: A Review of Joshua Mitts’ Proposal for a “Predictive Regulation” System

In Minority Report, Steven Spielberg’s futuristic movie set in 2050 Washington, D.C., three sibling “pre-cogs” are hooked up with wires and stored in a strange looking kiddie pool to predict the occurrence of criminal acts. The “Pre-Crime” unit of the local police, led by John Anderton (played by Tom Cruise), uses their predictions to arrest people before they commit the crimes, even if the person had no clue at the time that he or she was going to commit the crime. Things go a bit awry for Anderton when the pre-cogs predict he will commit murder. Of course, this prediction has been manipulated by Anderton’s mentor and boss to cover up his own past commission of murder, but the plot takes lots of unexpected twists to get us to that revelation. It’s quite a thriller, and the sci-fi element of the movie is really quite good, but there are deeper themes of free will and Big Government at play: if I don’t have any intent now to commit a crime next week, but the pre-cogs say the future will play out so that I do, does it make sense to arrest me now? Why not just tell me to change my path, or would that really change my path? Maybe taking me off the street for a week to prevent the crime is not such a bad idea, but convicting me of the crime seems a little tough, particularly given that I won’t commit it after all. Anyway, you get the picture.

As we don’t have pre-cogs to do our prediction for us, the goal of preventive government–a government that intervenes before a policy problem arises rather than in reaction to the emergence of a problem–has to rely on other prediction methods. One prediction method that is all the rage these days in a wide variety of applications involves using computers to unleash algorithms on huge, high-dimensional datasets (a/k/a/ Big Data) to pick up social, financial, and other trends.

In Predictive Regulation, Sullivan & Cromwell lawyer and recent Yale Law School grad Joshua Mitts lays out a fascinating case for using this prediction method in regulatory policy contexts, specifically the financial regulation domain. I cannot do the paper justice in this blog post, but his basic thesis is that a regulatory agency can use real-time computer assisted text analysis of large cultural publication datasets to spot social and other trends relevant to the agency’s mission, assess whether its current regulatory regime adequately accounts for the effects of the trend were it to play out as predicted, and adjust the regulations to prevent the predicted ill effects (or reinforce or take advantage of the good effects, one would think as well).

To demonstrate how an agency would do this and why it might be a good idea at least to do the text analysis, Mitts examined the Google Ngram text corpus for 2005-06, which consists of a word frequency database of the texts of a lot of books (it would take a person 80 years to read just the words from books published in 2000) for two-word phrases (bi-grams) relevant to the financial meltdown–phrases like “subprime lending,” “default swap,” “automated underwriting,” and “flipping property”–words that make us cringe today. He found that these phrases were spiking dramatically in the Ngram database for 2005-06 and reaching very high volumes, suggesting the presence of a social trend. At the same time, however, the Fed was stating that a housing bubble was unlikely because speculative flipping is difficult in homeowner dominated selling markets and blah blah blah. We know how that all turned out. Mitts’ point is that had the Fed been conducting the kind of text analysis he conducted ex post, they might have seen the world a different way.

Mitts is very careful not to overreach or overclaim in his work. It’s a well designed and executed case study with all caveats and qualifications clearly spelled out. But it is a stunningly good example of how text analysis could be useful to government policy development. Indeed, Mitts reports that he is developing what he calls a “forward-facing, dynamic” Real-Time Regulation system that scours readily available digital cultural publication sources (newspapers, blogs, social media, etc.) and posts trending summaries on a website. At the same time, the system also will scour regulatory agency publications for the FDIC, Fed, and SEC and post similar trending summaries. Divergence between the two is, of course, what he’s suggesting agencies look for and evaluate in terms of the need to intervene preventively.

For anyone interested in the future of legal computation as a policy tool, I highly recommend this paper–it walks the reader clearly through the methodology, findings, and conclusions, and sparks what in my mind if a truly intriguing set of policy question. There are numerous normative and practical questions raised by Mitts’ proposal not addressed in the paper, such as whether agencies could act fast enough under slow-going APA rulemaking processes, whether agencies conducting their own trend spotting must make their findings public, who decides which trends are “good” and “bad,” appropriate trending metrics, and the proportionality between trend behavior and government response, to name a few. While these don’t reach quite the level of profoundness evident in Minority Report, this is just the beginning of the era of legal computation. Who knows, maybe one day we will have pre-cogs, in the form of servers wired together and stored in pools of cooling oil.

Beyond Black Swans: The Dragon Kings of Climate Change

Weird stuff happens. Sometimes really weird stuff happens. And sometimes freaky weird stuff happens–the kind of events that just don’t fit the imaginable.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s 2007 book Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable, had a huge impact on our understanding of weird and really weird events. The essence of Taleb’s Black Swan theory:

What we call here a Black Swan (and capitalize it) is an event with the following three attributes.

First, it is an outlier, as it lies outside the realm of regular expectations, because nothing in the past can convincingly point to its possibility. Second, it carries an extreme ‘impact’. Third, in spite of its outlier status, human nature makes us concoct explanations for its occurrence after the fact, making it explainable and predictable.

I stop and summarize the triplet: rarity, extreme ‘impact’, and retrospective (though not prospective) predictability. A small number of Black Swans explains almost everything in our world, from the success of ideas and religions, to the dynamics of historical events, to elements of our own personal lives.

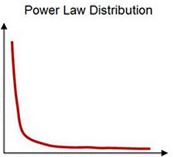

The key to preparing for Black Swans rests in understanding the way events are statistically distributed over time. Unlike the normal distribution found in many phenomena, such as SAT scores, other phenomena follow what is known as a power law distribution, with many small events and few large events. Think forest fires. Black Swan provided a compelling account of the problem of over-relying on normal distributions to explain the world. For problems defined by “fat tail” power laws that have outlier events way out on the tail one would not find on a normal distribution, sooner or later an event at the end of that tail is going to hit, and it’s going to be big. So, planning for some policy problem based on a normal distribution can lead to under-preparation if in fact the problem follows a power law distribution.

Well, here’s the thing–it’s worse than that. A recent article by Didier Sornette of the Department of Physics and Earth Science at ETH Zurich, Dragon-Kings, Black Swans and the Prediction of Crises, discusses what he calls “life beyond power laws,” meaning “the existence of transient organization [of a system] into extreme events that are statistically and mechanistically different from the rest of their smaller siblings.” In short, he documents the existence of “genuine outliers,” events which don’t even follow the power law distribution. (In the power law graph shown above, sprinkle a few dots way out to the right of the chart and off the line.) The Black Swan event isn’t really an outlier, in other words, because it follows the power law and is simply an event way out on the tail. Genuine outliers violate the power law–they are even “wilder” than what would be predicted by the extrapolation of the power law distributions in their tails. A classic example is Paris–whereas all the populations of all other cities in France map well onto a power law, Paris is a genuine outlier. But Sornette documents that other such outliers exist in phenomena as varied as financial crashes, materials failure, turbulent velocities, epileptic seizures, and earthquakes. He calls such events Dragon Kings: dragon for “different kind of animal” and king to refer to the wealth of kings, which historically has been an outlier violating power law distributions of the wealth of their citizens. (Dragon Kings are also mythical Chinese shapeshifting deities ruling over water, as well as the name of some pretty good Chinese restaurants in cities around the U.S. according to Yelp.)

So, what causes Dragon Kings? Sornette’s theory is complex, but boils down largely to instances when, for whatever reason, all of the feedback mechanisms in a system harmonize in one coupled, self-reinforcing direction. Massive outlier earthquakes, for example, are the result of “interacting (coupled) relaxation threshold oscillators” within the earth’s structure, and massive outlier financial crashes are the result of “the unsustainable pace of stock market price growth based on self-reinforcing over-optimistic anticipation.”

What’s the lesson? The key to Dragoon Kings is that they are the result of the same system properties that give rise to the power law, but violate the power law because those properties have become arranged in such a way as to create severe instability in the system–a systemic risk of failure. When all feedback in the system has harmonized in the same self-reinforcing direction, a small, seemingly non-causal disruption to the system can lead to massive failure. As Sornette puts it: “The collapse is fundamentally due to the unstable position; the instantaneous cause of the collapse is secondary.” His assessment of the financial crash, for example, that, like other financial bubbles, over time “the expectation of future earnings rather than the present economic reality that motivate[d] the average investor.” What pops the bubble might seem like an inconsequential event in isolation, but it is enough to set the collapse in motion. “Essentially, anything would work once the system is ripe.” And the financial system keeps getting ripe, and the bubbles larger, because humans are essentially the same greed-driven creatures they were back centuries ago when the Tulip Bubble shocked the world, but the global financial system allows for vastly larger resources to be swept into the bubble.

The greater concern for me, however, lies back in the physical world, with climate change. Sornette did not model the climate in his study, because we have never experienced and recorded the history of a genuine outlier “climate bubble.” But the Dragon King problem could loom. We don’t really know much about how the global climate’s feedback systems could rearrange as temperatures rise. If they were to begin to harmonically align, some small tipping point–the next tenth of a degree rise or the next ppm reduction in ocean water salinity–could be the pin that pops the bubble. That Dragon King could make a financial crisis look like good times….

Twitter Made Me Do It! – New Legal Issues Emerging from Advances in the Science of Social Networks

Advances in neuroscience and genetics have opened up profound and difficult legal issues regarding individual behavior. For example, before her tragic death the late Jamie Grodsky published a set of stunningly good articles on the impacts of genetics science on environmental law and toxic torts, and my colleague at Vanderbilt, Owen Jones, heads a vast research project on neuroscience and the law.

But at the other end of the spectrum, rapid advances are also underway in how we understand crowd behavior, and there are legal issues waiting to boil over. Like many of the issues covered in Law 2050, these advances are the direct result of the Big Data-computation combo, in this case aimed at the science of social networks (and I’m not just talking about the NSA…uh-oh, probably by just saying that they’ll start following my posts!). Of course we all know that Big Brother and even our friends and businesses are snooping through our social media. As the International Business Times reported earlier this week, for example, insurance companies scour claimant’s social media posts at the time of the accident to detect fraud, admissions of fault, and so on. My focus here is different–it’s on how we can learn what an individual does from studying his or her social network behavior, not just what he or she communicates to it (see here for a great summary of legal issues surrounding the latter).

For example, researchers studying the equivalent of Twitter in China, Weibo, reached findings about the flow of emotions in social network suggesting that anger spreads faster than does joy. As they summarize their paper‘s findings:

Recent years have witnessed the tremendous growth of the online social media. In China, Weibo, a Twitter-like service, has attracted more than 500 million users in less than four years. Connected by online social ties, different users influence each other emotionally. We find the correlation of anger among users is significantly higher than that of joy, which indicates that angry emotion could spread more quickly and broadly in the network. While the correlation of sadness is surprisingly low and highly fluctuated. Moreover, there is a stronger sentiment correlation between a pair of users if they share more interactions. And users with larger number of friends posses more significant sentiment influence to their neighborhoods. Our findings could provide insights for modeling sentiment influence and propagation in online social networks.

It’s only a matter of time before clever lawyers start using similar techniques to inform questions of intent, motive, reputation, liability, and so on. For example, if it could be shown that a person’s social media network flared up with anger (e.g., hostile comments or rumors about a spouse) shortly before the person committed a crime, that could prove influential in determining motive. Similarly, social network analytics could be used to measure the reputation impact of alleged libel or slander, consumer confusion in trademark infringement claims, and market perceptions in shareholder derivative claims–basically, anything that involves crowd behavior. Of course, there will also be a swarm of related legal issues such as privacy, data breaches, and admissibility in legal proceedings. So, just as scientific advances at the genetic and brain level are fueling legal issues regarding the individual, so too are advances in the science of social networks likely to open up new legal issues regarding crowds as crowds as well as their impacts on individuals.

What You Get When 45 Law Students Brainstorm About Legal Futures

Last week my Law 2050 class moved into a group project phase. I’ve divided the 45 students into six groups. Each group is exploring a pair of legal future topics grouped under two themes: (1) emerging legal technologies and practice models, and (2) future legal practice scenarios. The six paired topics are:

|

Group |

Tech/Industry Theme |

Practice Scenario Theme |

|

1 |

Outsourcing |

Environment and energy |

|

2 |

Legal process management |

Social and demographic |

|

3 |

Legal risk management |

Economic and financial |

|

4 |

Routinized and expert systems |

Health and medicine |

|

5 |

Legal prediction |

Data and privacy |

|

6 |

New legal markets | Other technologies |

Each group member prepared a proposed set of specific research projects fitting the group’s topics, and last week they pitched them to their groups. Each group selected 3-4 projects for each topic. They are exploring the viability of their tech/practice model selections and of their practice development selections. Later in the semester the groups will present their findings to the class as a whole.

Last week, the groups selected their final set of research projects and gave a quick summary to the class. I was quite impressed with the breadth and depth of their selections:

Future Practice Development Topics: synthetic organs, bitcoins, robotic surgery, student loan debt relief, Cloud computing, Google glass, 3-D printing, Dodd-Frank aftermath, crowdfunding, sea level rise, cybersecurity standards, carbon sequestration, space law & asteroid mining, virtual real estate, ocean-based power sources, biometric identification, water rights issues, genetically pre-fabricated children, natural disaster law, AI decision making, majority-minority America, same sex marriage, LGBTQIA rights, mass human migration, the sharing economy.

Legal Tech and Practice Models: QuisLex, Yuson & Irvine, LPO security breach issues, rebundling of LPO functions, My Case, Onit, Clerky, Axiom, Lex Machina, Casetext, Clearspire, Lawyer Up, Jury Verdict Analyzer, Kiiac, Neota Logic, healthcare compliance software.

I’m looking forward to what they have to say about each of these!

The Law and “Ultrafast Extreme Events” – Is it Possible to Regulate “Machine Ecology” If it Moves Faster than the Human Mind Can React?

In a fascinating new article in Nature’s Scientific Reports, researchers describe a “machine ecology” humans have built through which we have ceded decisionmaking across a wide array of domains to technologies moving faster than the human mind can react. Consider that the new transatlantic cable underway is being built so we can reduce communication times by another 5 milliseconds, and that a new chip designed for financial trading can execute trades in just 740 nanoseconds (that’s 0.00074 milliseconds!), whereas even in its fastest modes (flight from danger and competition) the human mind makes important decisions in just under 1 second. As the article abstract suggests, the proliferation of this machine ecology could present as many problems as benefits:

Society’s techno-social systems are becoming ever faster and more computer-orientated. However, far from simply generating faster versions of existing behaviour, we show that this speed-up can generate a new behavioural regime as humans lose the ability to intervene in real time. Analyzing millisecond-scale data for the world’s largest and most powerful techno-social system, the global financial market, we uncover an abrupt transition to a new all-machine phase characterized by large numbers of subsecond extreme events. The proliferation of these subsecond events shows an intriguing correlation with the onset of the system-wide financial collapse in 2008. Our findings are consistent with an emerging ecology of competitive machines featuring ‘crowds’ of predatory algorithms, and highlight the need for a new scientific theory of subsecond financial phenomena.

One has to wonder how we can design regulatory mechanisms that will prove effective in controlling “ultrafast extreme events” and how legal doctrine will handle issues of liability, property, and contract when such events are moving at nanosecond speeds beyond human recognition. Indeed, the article’s authors focus on the financial system, and observe that the extent to which the thousands of UEEs their research has detected as occurring during the financial crisis were actually “provoked by regulatory and institutional changes around 2006, is a fascinating question whose answer depends on a deeper understanding of the market microstructure.” I’d love to see how Congress tees up that committee hearing!

Insights on the “New Normal” from Law Firm Managing Partners and Corporate Counsel

Last week in my Law 2050 class we held two panels of speakers–a panel of three BigLaw managing partners on Monday (Ben Adams of Baker Donalson, Richard Hayes of Alston Bird, and Steve Mahon of Squire Sanders) followed by a panel of three in-house counsel of large corporations (Reuben Buck of Cisco, Jim Cuminale of Nielsen, and Cheryl Mason of Hospital Corp. of America). First, my enthusiastic thanks to our panelists, who provided a lively, engaging, deep, and quite candid forum for the students.

Indeed, the speakers covered so much ground I could not possibly cover it all in one or even several posts. So what rose to the top in my assessment? Four things:

- The Rise of MediumLaw. Both sets of speakers suggested that medium-sized firms (MediumLaw) are increasingly a source of competition for BigLaw and of legal services to large corporations, confirming Richard Susskind’s prediction that, while MediumLaw firms will face pressures to consolidate, they now have “an unprecedented opportunity to be recognized as credible alternatives” to BigLaw. One reason is the basic “world is flat” effect, making it easy to access legal talent everywhere. As for legal talent, all the speakers recognized that MediumLaw is brimming with top legal talent. The there is the lower fee structure a client is likely to enjoy by hiring a regional MediumLaw to handle a matter in the region. While all the corporate counsel confirmed that “bet the company” litigation or massive, complex transactional work is likely to go to BigLaw because of its repository of experience on such matters and ability to scale up to a matter of any size, there was no question that they considered MediumLaw a substantial and growing source of their legal service needs.

- The Corrosive Effect of Lateral Partner Movement: Both sets of speakers emphasized the importance, now more than ever, of establishing strong relationships between firm and client. The corporate counsel stressed the need for firms to “know my business,” and the managing partners pointed to many new kinds of practices they are taking to get there. And both panels identified the acceleration of lateral partner movement as one of the chief obstacles. Indeed, when asked what keeps them up at night, the managing partners concurred that the fallout from actual and potential partner exits is a constant source of stress (though I imagine each of the firms represented has done its share of lateral partner hiring).

- Value: The corporate counsel kept coming back to their primary concern in selecting outside counsel—value, value, value. What wasn’t as clear is how clients evaluate it and how firms are rethinking how they deliver it. For example, Cisco is well-known for using fixed fees arrangements for much of its work, but one of the corporate counsel suggested that fixed fee is not necessarily the silver bullet. If the fixed fee is simply a number that aggregates the expected revenue from an hourly billing method, how is that delivering better value? My strong sense from this representative group was that while firms and clients are willing to experiment with ways to wean off of the billable hour, there is no consensus yet on what alternative fee model will consistently deliver better value over time.

- Law Firm Financial Structure as an Obstacle to Innovation: A strong theme the managing partners panel returned to several times was how the nature of partnerships as financial entities constrains innovation. Firms manage tax consequences by flushing out profits and limiting retained earnings, which puts a disincentive on investing in R&D and makes experimenting in costly new business models or products quite risky. To be sure, the managing partners described some innovative practices–for example, one firm maintains a “venture fund” in the form of an allotment of “billable” hours groups of attorneys can apply for to free them up for practice development projects, with the firm standing behind accounting for the hours as counting every bit as much as hours actually billed to clients. As the partner from that firm explained it, that kind of practice development project is highly valuable to the firm, but not to individual lawyers if they don’t get credit for it, so they won’t do it with this kind of incentive. Yet the appetite for that kind of innovation necessarily is limited by the partnership financial profile as well, not just by the billable hour itself.

This is just a taste of the range and depth of topics our panels covered. Again, I can’t thank them enough. as for my students, I know from the “buzz” that the panels made a tremendous impression on them. They handed in their reaction papers yesterday, so I will soon learn just what that impression was!

The President’s Climate Action Plan – What’s In it for Tomorrow’s Lawyers?

In June 2013 President Obama became the first U.S. president to issue a climate action plan. Needless to say it got a lot of press. Some climate change policy watchers panned it as nothing new (meaning no new proposals for regulation); others condemned it as, well, nothing new (meaning it keeps all the old proposals for regulation); and some praised it as visionary. That’s not my topic for this post. I want to ask what the Plan, whether it’s anything new or not, means for lawyers of the future.

I hope not to sound perverse in suggesting that there is opportunity for lawyers in climate change, but of course there is. Change of any kind often creates opportunities for lawyers, especially the ones who think about it before it happens. So I ask, what’s in the Plan for lawyers, particularly tomorrow’s lawyers–the kind I care about here at Law 2050?

A study commissioned by the Natural Resources Defense Council claims that the Plan–specifically, the part of the Plan that proposes to regulate carbon emissions–will create jobs. Alas, nowhere in that study does it mention new jobs for lawyers. Can it be that there will be no new opportunities for lawyers? I doubt it. Rather, to paraphrase Mr. McGuire from The Graduate: I want to say three words to you. Just three words: Energy and Land Use. OK, I guess that’s four words, but let me get to the point.

As with most climate change policy discourse, there are two main components to the Plan: (1) mitigation, which is how to reduce climate change, primarily by reducing carbon emissions (and/or increasing sinks), and (2) adaptation, which is how to respond to the climate change we will experience regardless of (1), particularly given that (1) isn’t exactly going gangbusters. So if you step back and look for the legal action in the Plan, Energy and Land Use should hit you in the face.

ENERGY: The Plan’s mitigation component is largely about energy policy. In fact, it may be the closest we’ve come to having a national energy policy, ever. Most of the headings in this part of the Plan contain the word energy or are energy focused, such as:

- cutting carbon pollution from power plants

- promoting American leadership in renewable energy

- accelerating clean energy permitting

- expanding and modernizing the electric grid

- unlocking Long-term investment in clean energy innovation

- spurring investment in advanced fossil energy projects

- instituting a Federal Quadrennial Energy review

- increasing fuel economy standards

- reducing energy bills

- establishing a new goal for energy efficiency standards

- reducing barriers to investment in energy efficiency

And the list goes on. Energy, Energy, Energy! Once again, Mr. McGuire said it for me: Tomorrow’s lawyers, there’s a great future in Energy Law. Think about it. Will you think about it?

LAND USE: Although more subtle in its delivery, the adaptation part of the Plan is largely about land use. In climate change policy speak, the term “resilience” is widely used to mean that we need to be better at handling effects of climate change, and a big part of that is about better planning for the built environment and its infrastructure. Plan headings that pop out in this respect include:

- building stronger and safer communities and infrastructure

- directing agencies to support climate-resilient investment

- supporting communities as they prepare for climate impacts

- boosting the resilience of buildings and infrastructure

- rebuilding and learning from Hurricane Sandy

- conserving land and water resources

- maintaining agricultural sustainability

- managing drought

- reducing wildfire risks

- preparing for future floods

There is more in the adaptation part, to be sure, including health, insurance, and science, but mostly its about…Land Use! Tomorrow’s lawyers, there’s a great future in Land Use Law. Think about it. Will you think about it?

The Artificial (Intelligence) Restatement of the Law?

As I write, the 2013 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and the Law is taking place in Rome. I wish I had been able to attend–anyone remotely interested in the scope of Law 2050 should take a look at the program.

Most of the discourse on AI and the Law in the popular press has focused on the capacity AI to predict the law, as with Lex Machina and Lexis’s MedMal Navigator. But if you take a close look at the ICAIL program, the sleeper may be the capacity of AI to make the law. Many of the presentations delve into methods of using algorithms to extract and organize legal principles from the vast databases or cases, statutes, and other legal sources now available. The capacity to produce robust, finely-grained, broad scope statements of what the law is powerful not only for descriptive purposes, but as a force in shaping the law as well.

Consider the American Law Institute’s long-standing Restatement of the Law project. As ALI explains,”the founding Committee had recommended that the first undertaking of the Institute should address uncertainty in the law through a restatement of basic legal subjects that would tell judges and lawyers what the law was. The formulation of such a restatement thus became ALI’s first endeavor.” As I think any lawyer would agree, the idea worked pretty well, pretty well indeed. The Restatements have been so influential that they go well beyond describing the law–they contribute to making the law through the effect they have on lawyers arguing cases and judges reaching decisions.

How did ALI pull that off? Numbers. Anyone who has worked on a Restatement revision committee has experienced the incredible data collection and analytical powers that ALI assembles by gathering large numbers of domain experts and tasking them with distilling the law of a field into its core elements and extended nuances. The process, however, is protracted, costly, tedious, and often contentious.

Many of the ICAIL programs suggest the capacity of AI to generate the same kind of work product as ALI’s Restatements, but faster, cheaper, and perhaps better. ALI depends on large committees of experts to gather case law, analyze it, and extract and organize the underlying doctrines and principles. That’s exactly what AI for law does, only with a lot fewer people, a lot more data, and amazingly efficient and effective algorithms. Of course, you still (for now) need people to manage the data and develop the algorithms, but once you have it all in place you just hit the run button. When you want an update, you just hit the run button again. When you want to ask a question in a slightly different way, just enter it and hit the run button.

As the Restatements demonstrated, a reliable, robust source of reference for what the law is can be so influential as to become a part of the making of the law. As AI applications build the capacity to replicate that work product, it follows that they could have the same kind of influence.

One feature AI could not produce, of course, is the commentary and policy pushing one finds in the Restatements. The subjective dimension of the Restatements has its own pros and cons. The potential of AI to produce highly-accurate, real-time descriptions of the law, however, might change the way in which we approach normative judgments about the law as well.

On Systemic Risk and the Legal Future

If you’ve heard the term “systemic risk” it was most likely in connection with that little financial system hiccup we’re still recovering from. But the concept of systemic risk is not limited to financial systems–it applies to all complex systems. I have argued in a forthcoming article, for example, that complex legal systems experience systemic risk leading to episodes of widespread regulatory failure.

Dirk Helbing of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology has published an article in Nature, Globally Networked Risks and How to Respond, that does the best job I’ve seen of explaining the concept of systemic risk and relating it to practical contexts. He defines systemic risk as

the risk of having not just statistically independent failures, but interdependent, so-called “cascading” failures in a network of N interconnected system components. That is, systemic risks result from connections between risks (“networked risks”). In such cases, a localized initial failure (“perturbation”) could have disastrous effects and cause, in principle, unbounded damage as N goes to infinity….Even higher risks are multiplied by networks of networks, that is, by the coupling of different kinds of systems. In fact, new vulnerabilities result from the increasing interdependencies between our energy, food and water systems, global supply chains, communication and financial systems, ecosystems and climate.

As Helbing notes, the World Economic Forum has described this global environment as a “hyper-connected” world exposed to massive systemic risks. Helbing’s paper does a wonderful job of working through through the drivers of systemic instability (such as tipping points, positive feedback, and complexity) and explaining how they affect various global systems (such as finance, communications, and social conflict). Along the way he makes some fascinating observations and poses some important questions. For example:

- He suggests that catastrophic damage scenarios are increasingly realistic. Is it possible, he asks, that “our worldwide anthropogenic system will get out of control sooner or later” and make possible the conditions for a “global time bomb”?

- He observes that “some of the worst disasters have happened because of a failure to imagine that they were possible,” yet our political and economic systems simply are not wired with the incentives needed to imagine and guard against these “black swan” events.

- He asks “if a country had all the computer power in the word and all the data, would this allow government to make the best decisions for everybody?” In a world brimming with systemic risk, the answer is no–the world is “too complex to be optimized top-down in real time.”

OK, so what’s this rather scary picture of our hyper-connected world got to do with Law 2050? Quite simply, we need to build systemic risk into our scenarios of the future. I argue in my paper that the legal system must (1) anticipate systemic failures in the systems it is designed to regulate, but also (2) anticipate systemic risk in the legal system as well. I offer some suggestions for how to do that, including greater use of “sensors” style regulation and a more concerted effort to evaluate law’s role in systemic failures. More broadly, Helbing suggests the development of a “Global Systems Science” discipline devoted to studying the interactions and interdependencies in the global techno-socio-economic-environmental system leading to systemic risk.

There is no way to root out systemic risk in a complex system–it comes with the territory–but we don’t have to be stupid about it. Helbing’s article goes a long way toward getting smart about it.

Law 2050 Looks at 2052

While on a post-free vacation the past week, I finished reading Jorgen Randers’ 2052: A Global Forecast for the Next Forty Years. (How could the author of a blog named Law 2050 resist reading a book titled 2052?) Randers is a Norwegian Business School professor specializing in climate strategy and scenario analysis, and was a coauthor of 1972’s The Limits to Growth, which, like 2052, was a report to the Club of Rome project. Unlike LTG, however, 2052 is not a scenario-building exercise (LTG developed 12 global scenarios through 2100). Rather, as Randers describes it, 2052 takes the LTG scenario Randers considers the most probable given the last 40 years of experience since LTG and plays it out in a global forecast for the next 40 years. The forecasting is based on computer modeling using extensive datasets organized around four major cause-and-effect themes: (1) population and consumption, (2) energy and CO2, (3) food and ecological footprint, and (4) a collection of economic, social, and demographic factors. After a macro-view of trends in these categories, all of which point to an “overshoot” in our use of resources, Randers then provides sub-global forecasts for the US, China, OECD (minus US), BRISE (BRIC minus China but plus some others), and rest of the world. Along the way 2052 sprinkles in dozens of micro forecasts by other experts on a variety of pertinent topics.

2052 is a marvelous book, well worth the long, dense read. There’s far more to it than I could possibly summarize here, but a few points seem pertinent to Law 2050‘s scope:

- Randers predicts a world in which climate change is a major driver leading to a global infusion of energy efficiency technology and renewable energy infrastructure. Whereas LTG foresaw scenarios of overshoot dealt with through managed decline, Randers believes that the climate problem has moved us past overshoot into an era of “collapse induced by nature.” We will need energy efficiency and renewable energy just to tread water. Message for Law 2050: Energy law is going to grow only more important and broader in scope over the next 40 years.

- The US and OECD will move into a period of stagnation as population levels off and we must pay for the self-indulgence of current and prior generations financed on unsustainable fiscal structures and deferred infrastructure investment. Hindering their ability to pull out of this dive will be the short-term focus of modern democratic politics and capitalism, which ultimately will prevent the US and many OECD nations form making necessary adjustments for the long-term. China, meanwhile, with its centralized governance system and economy will become the dominant global economic force, requiring most other nations to march to its trade policy tune. Message for Law 2050: Start thinking about what it means for the US economy to look much like it does now for a long time while China slowly but surely becomes the center of global trade and policy.

- There is going to be social unrest across many scales. Many poor people in the world will be much better off than they are today, but many will not and the rich nations will experience declining growth and income. In the US, one lightening rod will be growing tension between the baby-boomers and their children and grandchildren, with Randers predicting that as the young become politically dominant they will simply say no to the prospect of maintaining the levels of support the baby-boomers unilaterally awarded themselves by leaving the bill on the table for younger generations to pick up. Message for Law 2050: There’s going to be some messy legal wrangling over how to pay for all that dessert the baby-boomers want to eat, and whether they’ll get all they ordered.

- Randers acknowledges some “wild card” scenarios that could throw his forecast off track, including the continued pushing off of peak oil, another financial meltdown, nuclear war, and revolution in a major nation such as the US or China. Notably, however, radical technological change is not one of his wild cards, nor does it play much of a role in the forecast generally. Message for Law 2050: Forecasts are tricky–keep building multiple scenarios and don’t ever underestimate technology.

For all it covers, however, 2052 makes no mention of legal evolution in its forecast. Randers assumes (probably with good reason given the record so far) that the international community will not rally around climate with any meaningful international law response (listing that as one of wild cards instead), but does not consider how law contributes to or could redirect or respond to any of the other trends he predicts at regional and national scales. Nevertheless, and perhaps as a consequence, Law 2050 will make frequent references to 2052 in the future as a robust base for building and testing scenarios of our legal future.